The Unwrapping of Tutankhamun’s mummified body, November 1925

The story of the unwrapping of the young king.

Among the many moments that marked the decade-long excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb, the unwrapping and examination of the king’s mummified body must surely be ranked as the most anticipated one.

It wasn't until the 4th excavation season, in the autumn of 1925, that it took place, because it had taken Howard Carter and his team nearly three years to painstakingly record and conserve the many objects discovered in the Antechamber and the Burial Chamber.

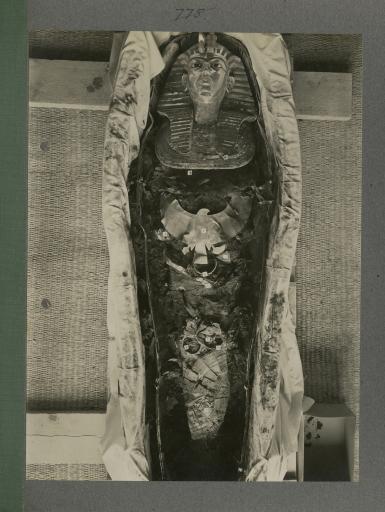

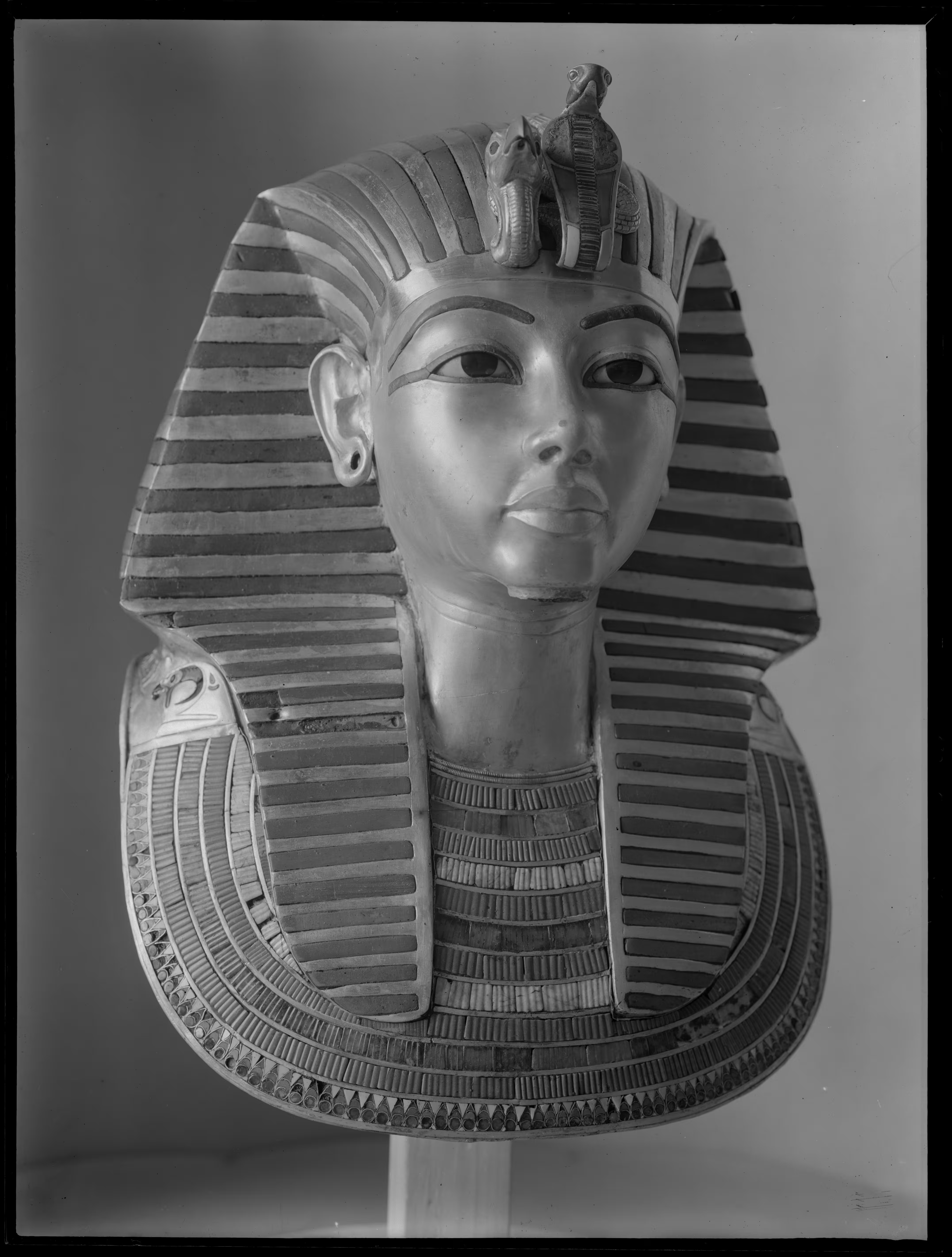

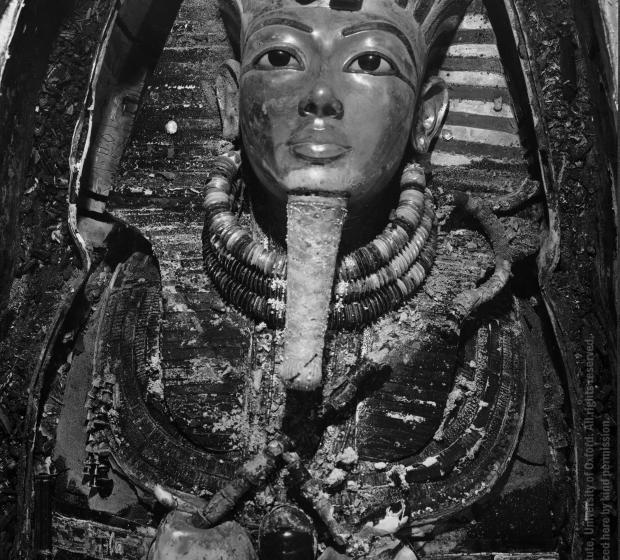

The body of Tutankhamun was discovered in the inner coffin, with the funerary mask protecting the king’s head and neck (Burton image, TAA i.5a.P0744).

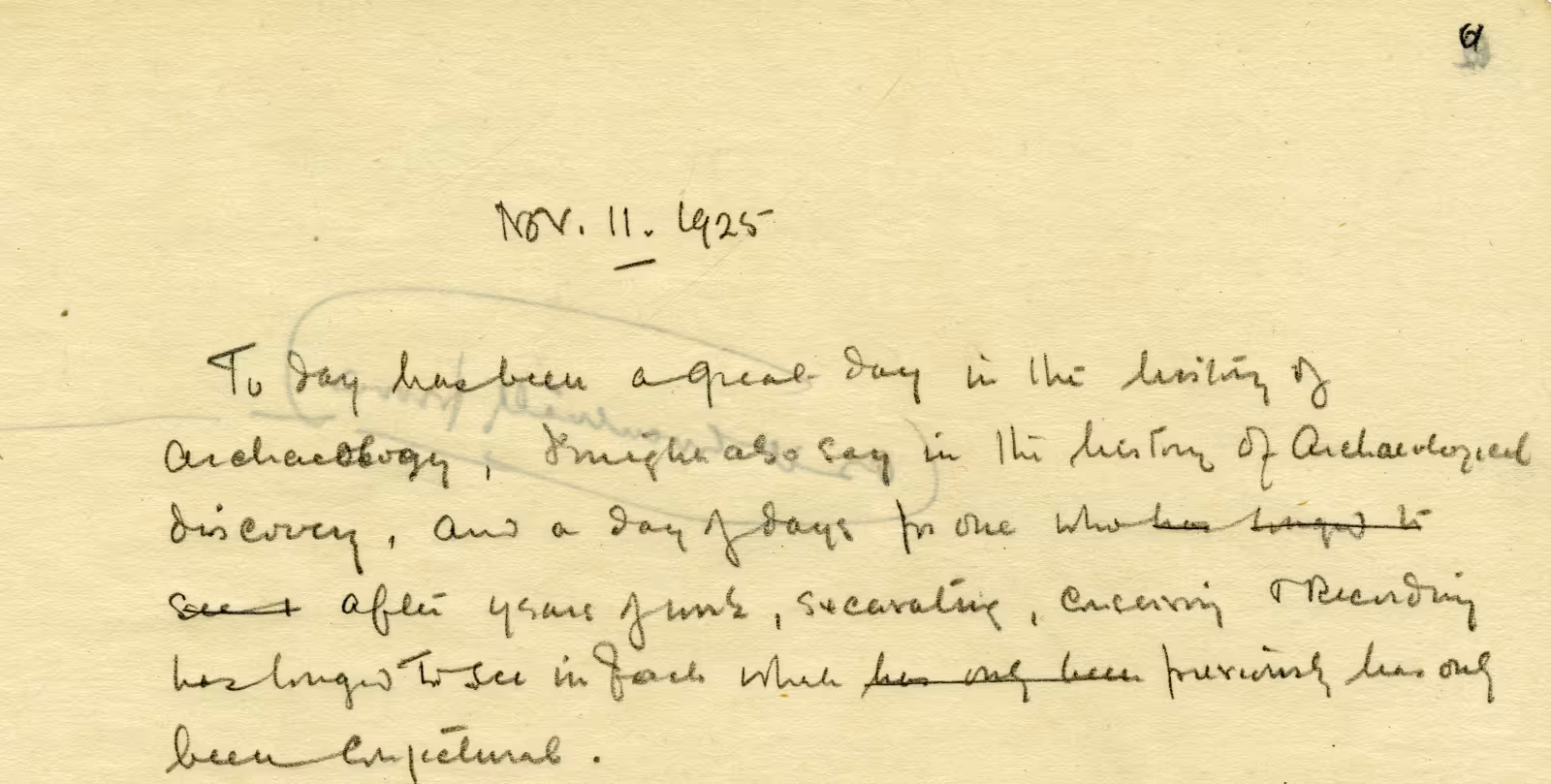

Howard Carter’s journal entry for the 11th of November 1925 (TAA i.2.3.61).

"Today has been a great day in the history of archaeology"

On the morning of 11 November 1925, at 9:45 a.m., a small group gathered in the nearby tomb of pharaoh Sety II (KV 15) where the coffin containing Tutankhamun’s body had been taken as it provided more space.

Carter was keenly aware of the magnitude of the event and his journal entry for the day reveals his awe: “Today has been a great day in the history of archaeology, I might also say in the history of archaeological discovery, and a day of days for one who after years of work, excavating, conserving & recording, has longed to see in fact what previously has only been conjectural.”

The unwrapping lasted nine days.

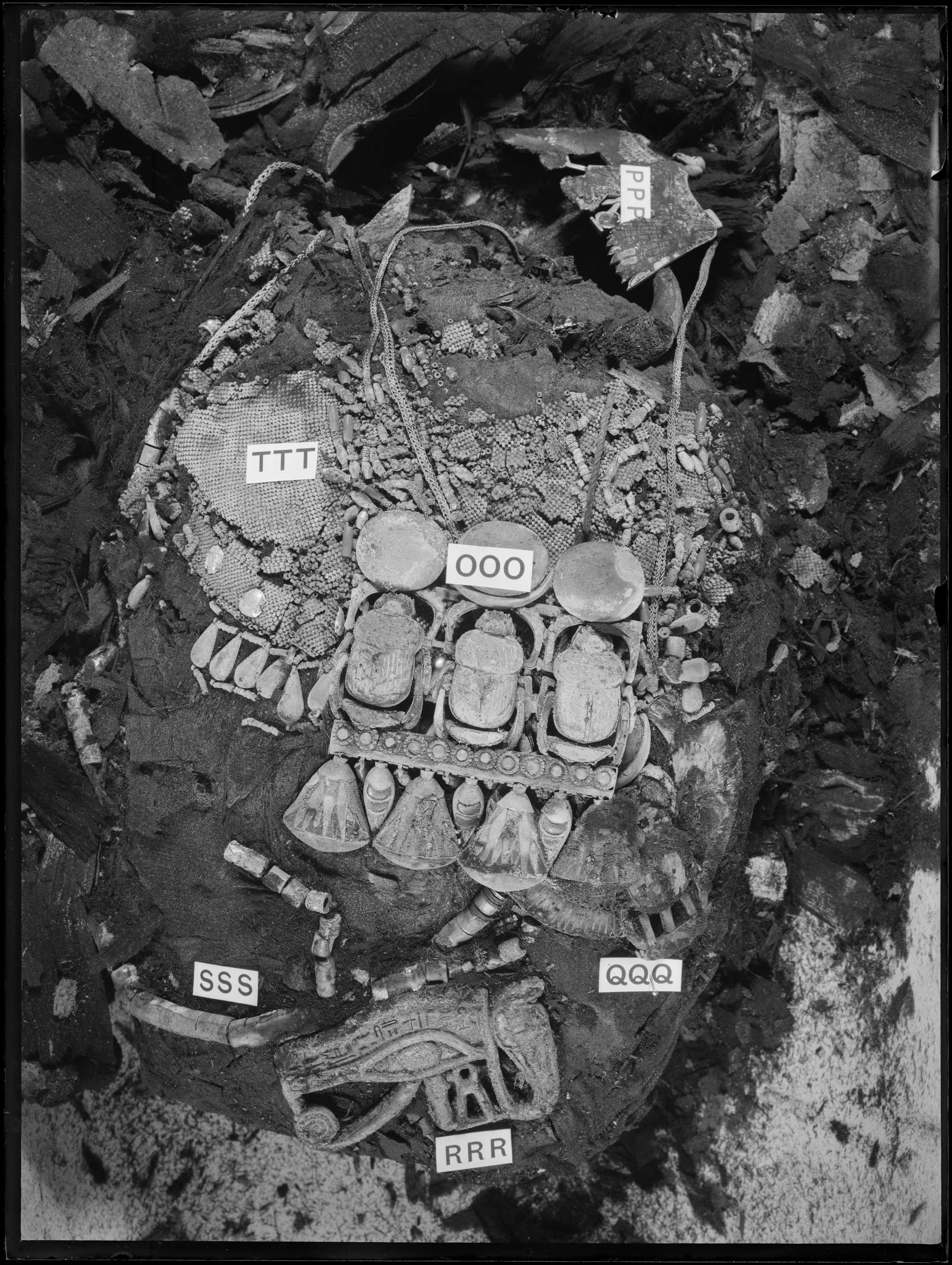

Objects found

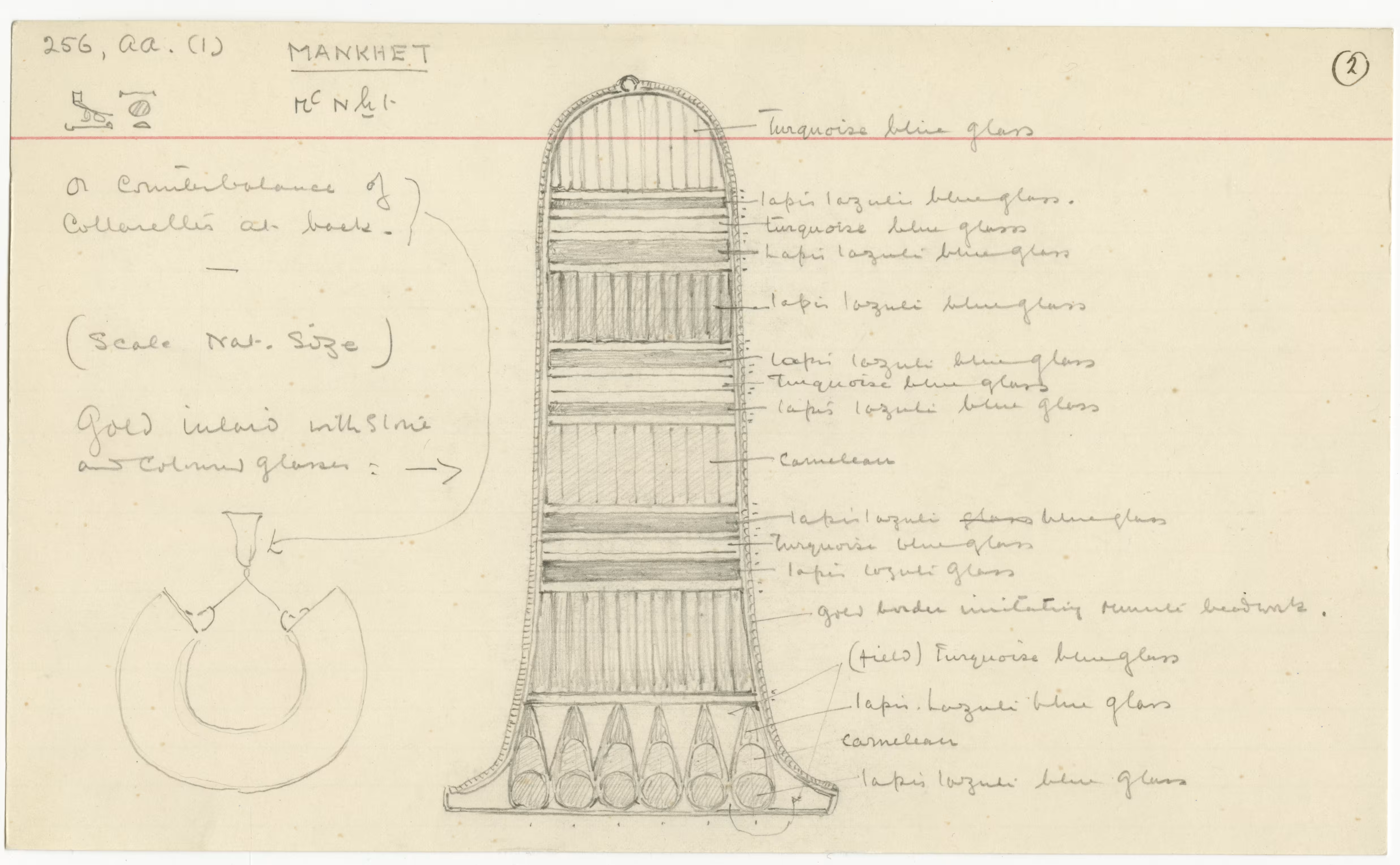

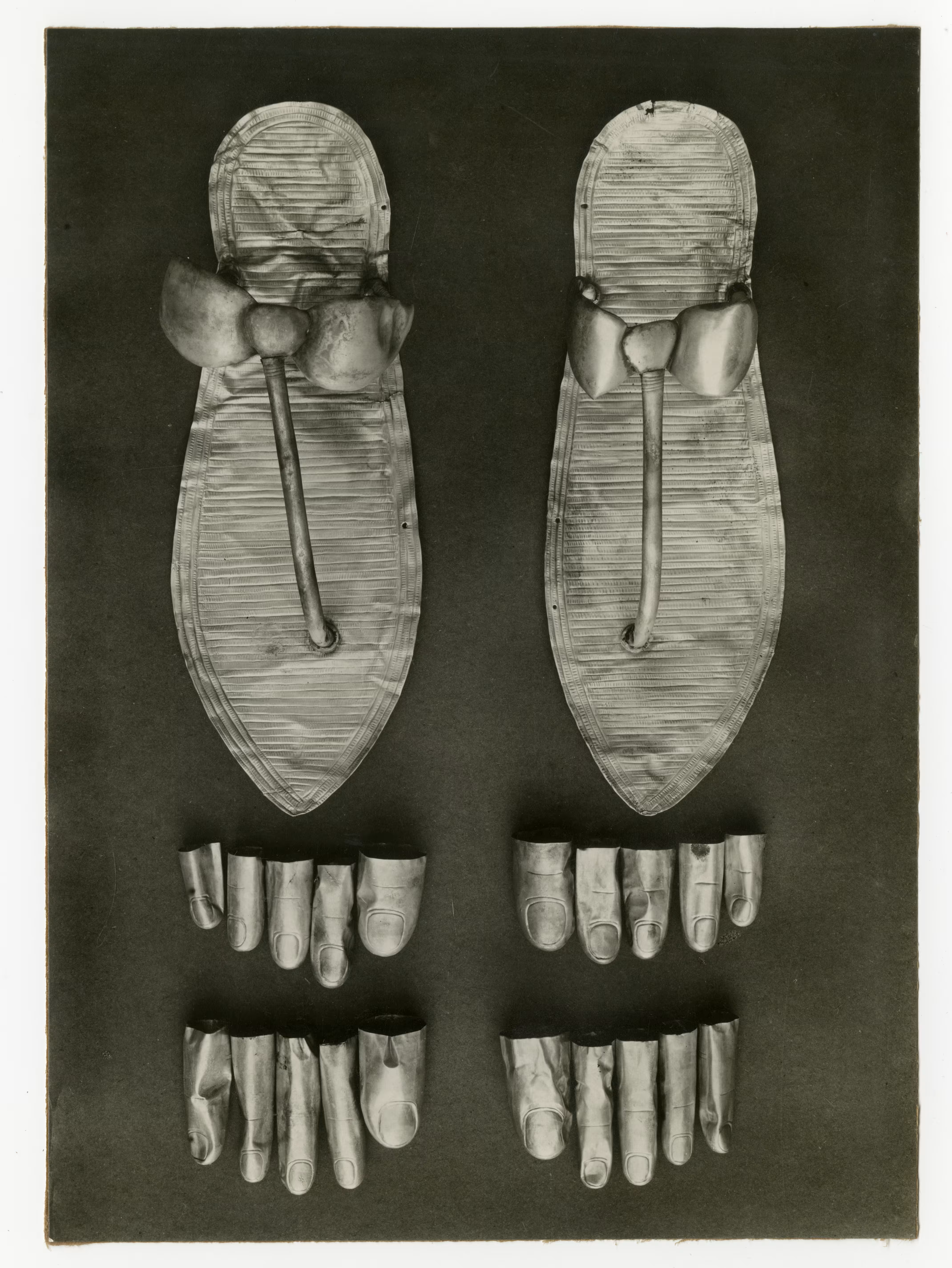

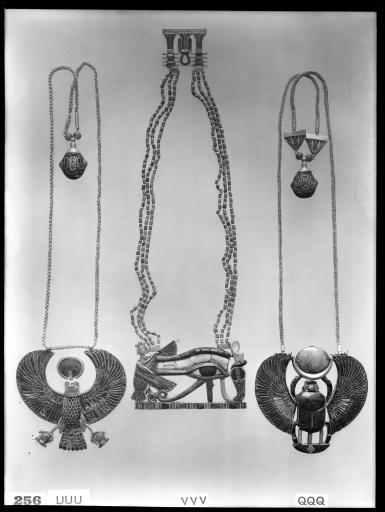

Altogether more than 100 objects were discovered inside the linen bandages such as amulets, golden stalls for Tutankhamun’s fingers and toes, two daggers, bracelets, rings, collars or pectoral.

It is clear that some of these artefacts were of purely ritual nature to protect the king’s body against injuries on his journey through the underworld, while some were of a very personal nature and probably used by the king during his lifetime. The craftsmanship astonished even Carter, who observed:

“it would tax our goldsmiths of today to surpass such refinement as is found in these royal ornaments.”

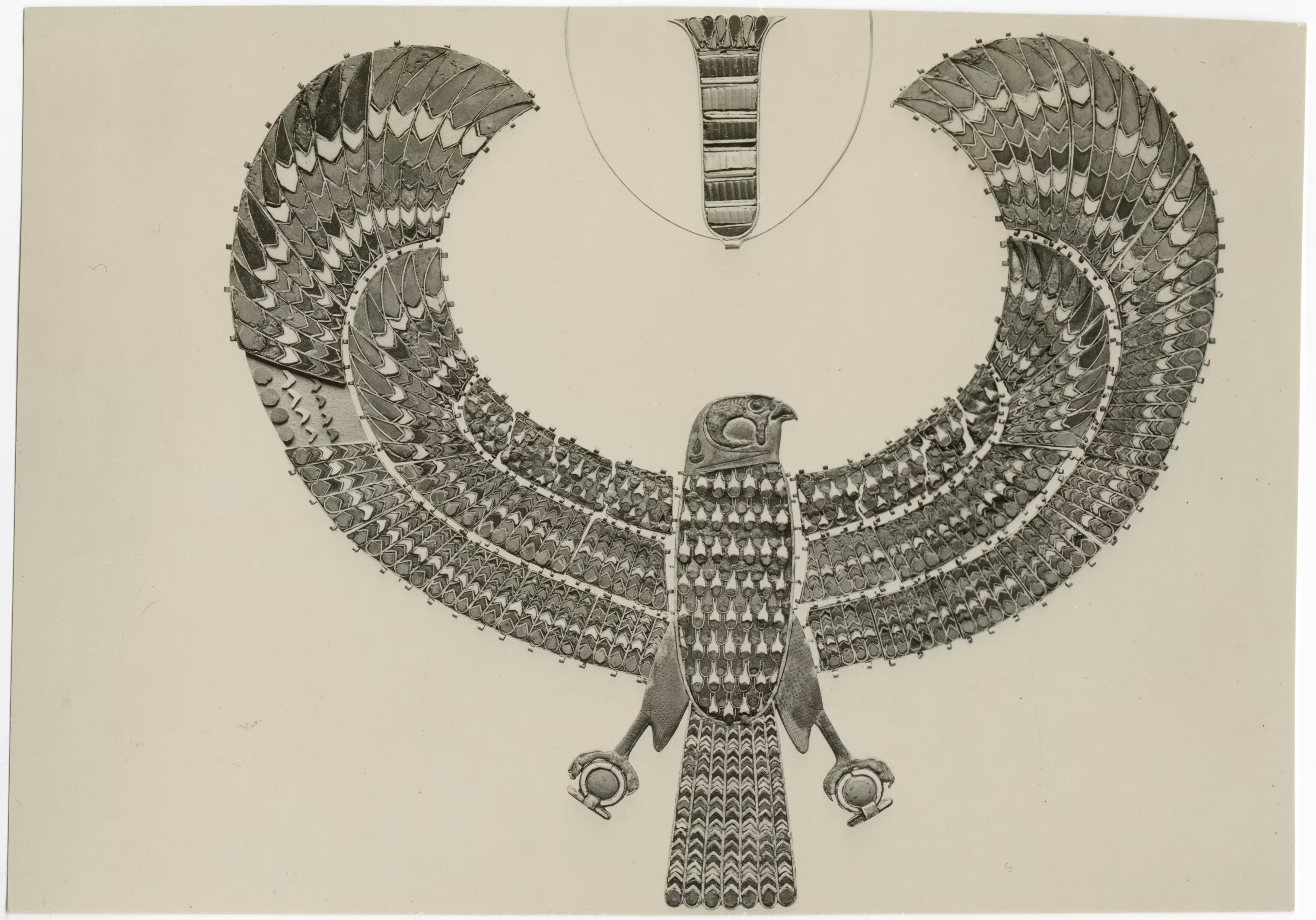

“Studio photograph” of three pectorals (256.uuu, 256.vvv and 256.qqq) discovered on the body of the king (Burton image TAA i.5.P0857a).

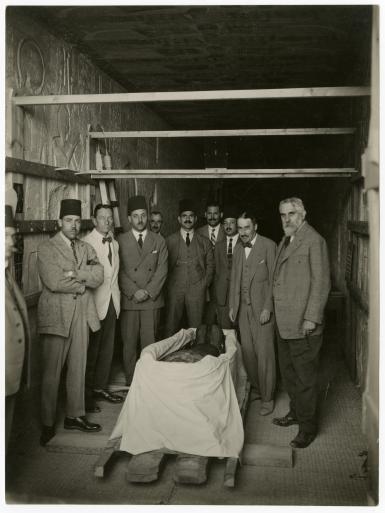

The official committee attending the unwrapping of Tutankhamun’s body, gathered in the tomb of Sety II (Burton image TAA i.5a.P1559).

The official committee

The examination was conducted under the authority of the Egyptian Antiquities Service. Present were Pierre Lacau, the Service’s director, and representatives of the Egyptian government, among them Saleh Enan Pasha, Sayed Fuad Bey El Kholi, Tewfik Effendi Boulos, Mohamed Effendi Shaban and Hamed Effendi Suliman.

Two medics —Dr Saleh Bey Hamdi, former Director of the Cairo Medical School, and Professor Douglas Derry, a British anatomist at the same institution—were responsible for the anatomical examination.

Also in attendance were the Egyptian members of staff attached to the excavation, along with Alfred Lucas, the expedition’s chemist and conservator, and Harry Burton who documented every stage in photographs.

Removing the wrappings

The outer layers of the linen wrappings had decayed to a fragile, powdery mass.

To stabilise the surface before any incision could be made, a thin coat of melted paraffin wax was brushed on. Once hardened, it allowed Derry to begin cutting through the wrappings, removing them layer by layer.

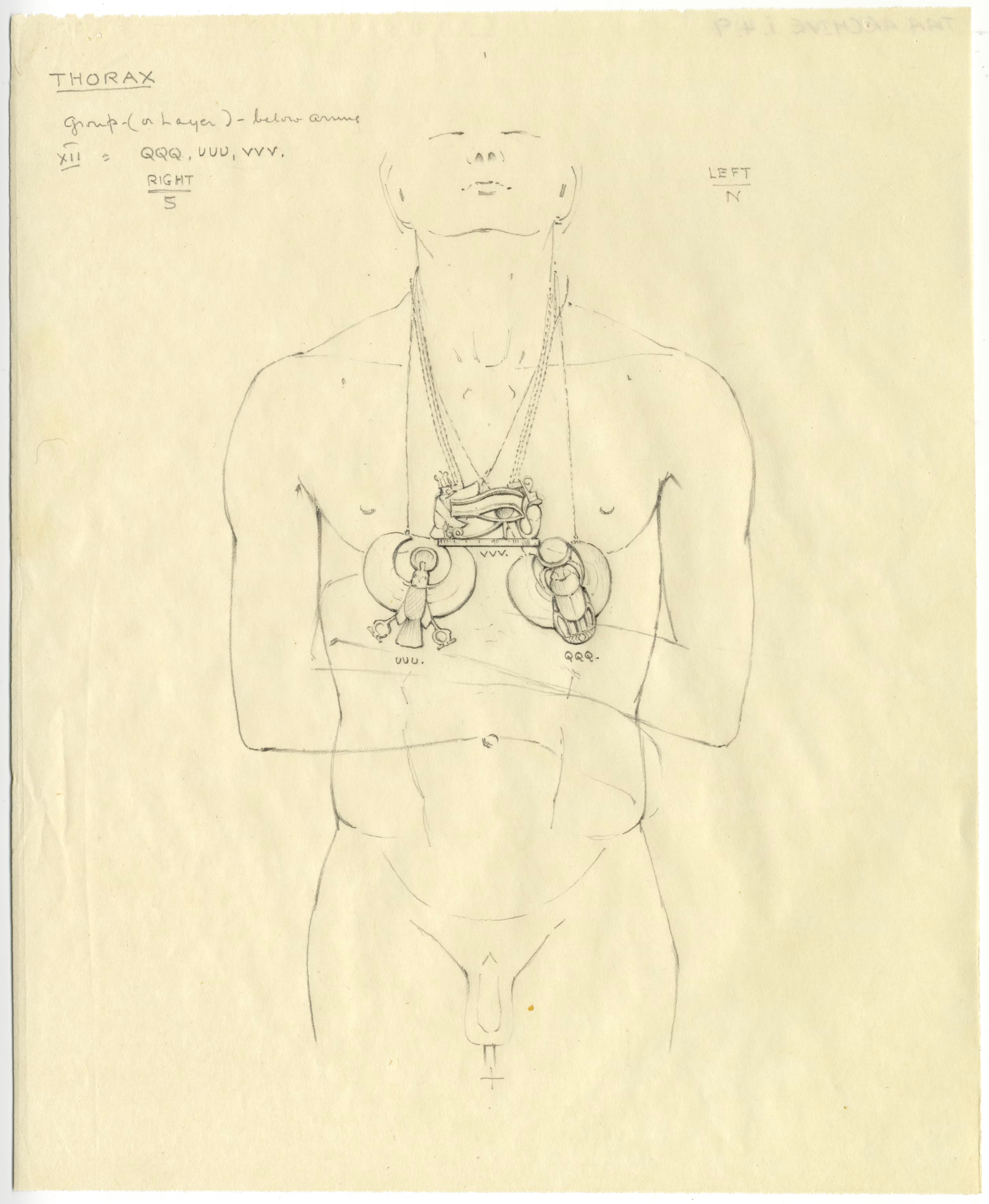

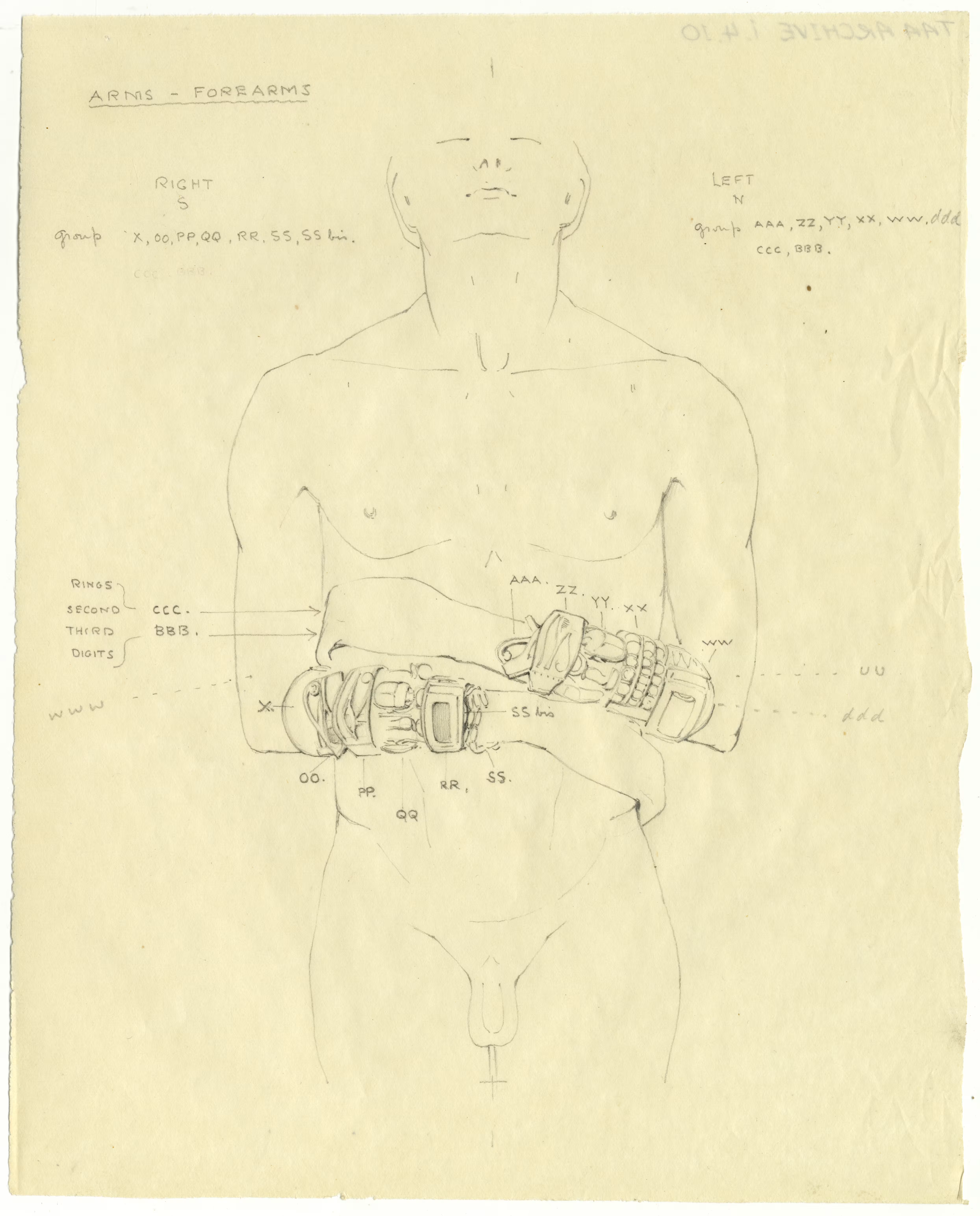

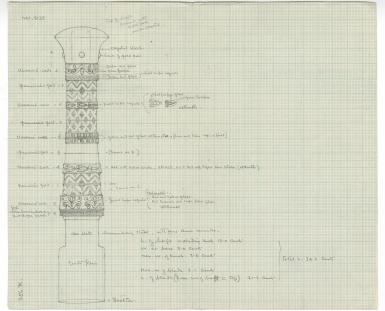

The position of each object was carefully recorded: Harry Burton took images of the artefacts as they were found, in situ, then Carter assigned individual numbers to each object, small numbers cards were placed next to the artefacts, and Harry Burton took more images.

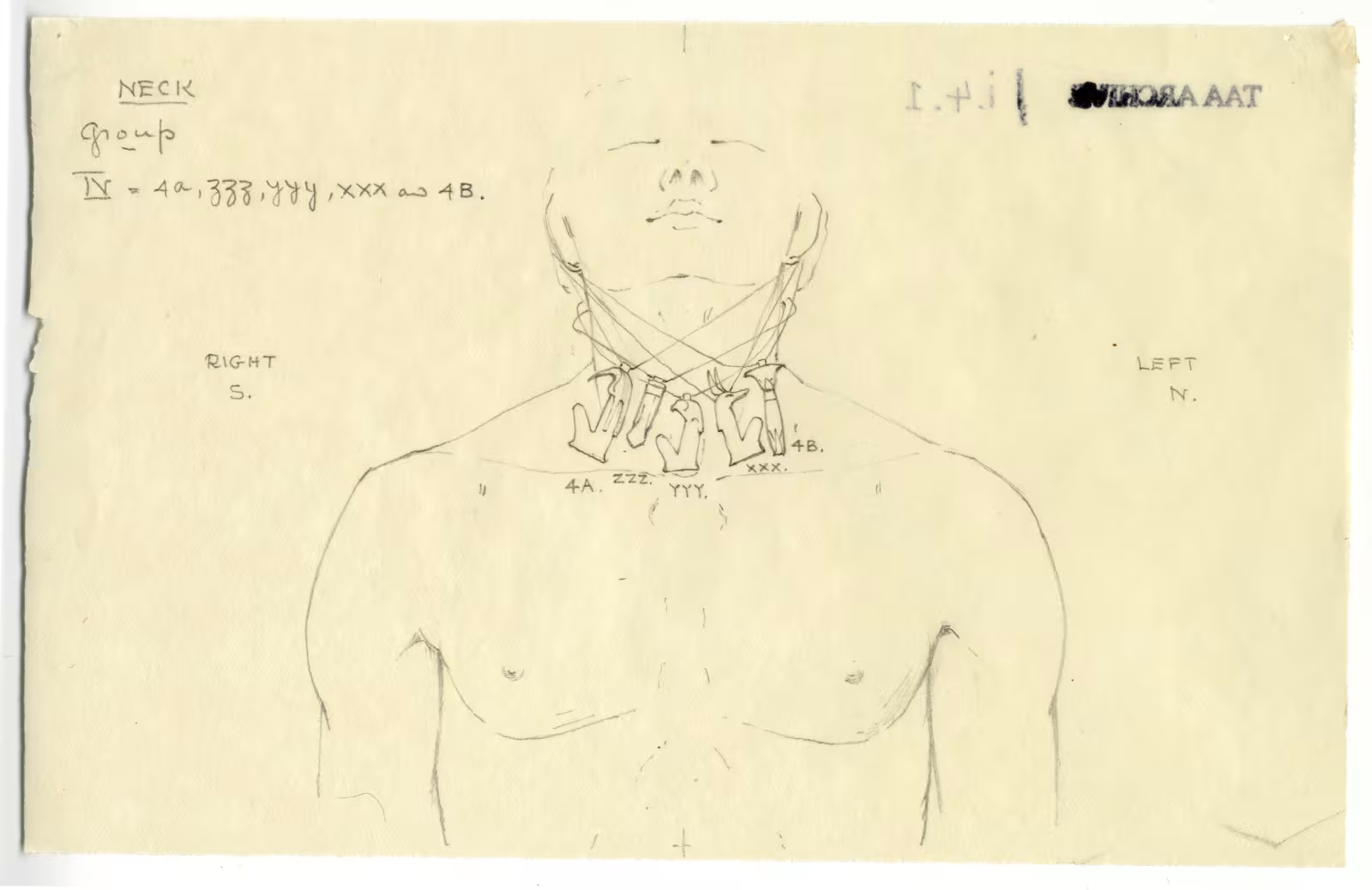

The autopsy drawings

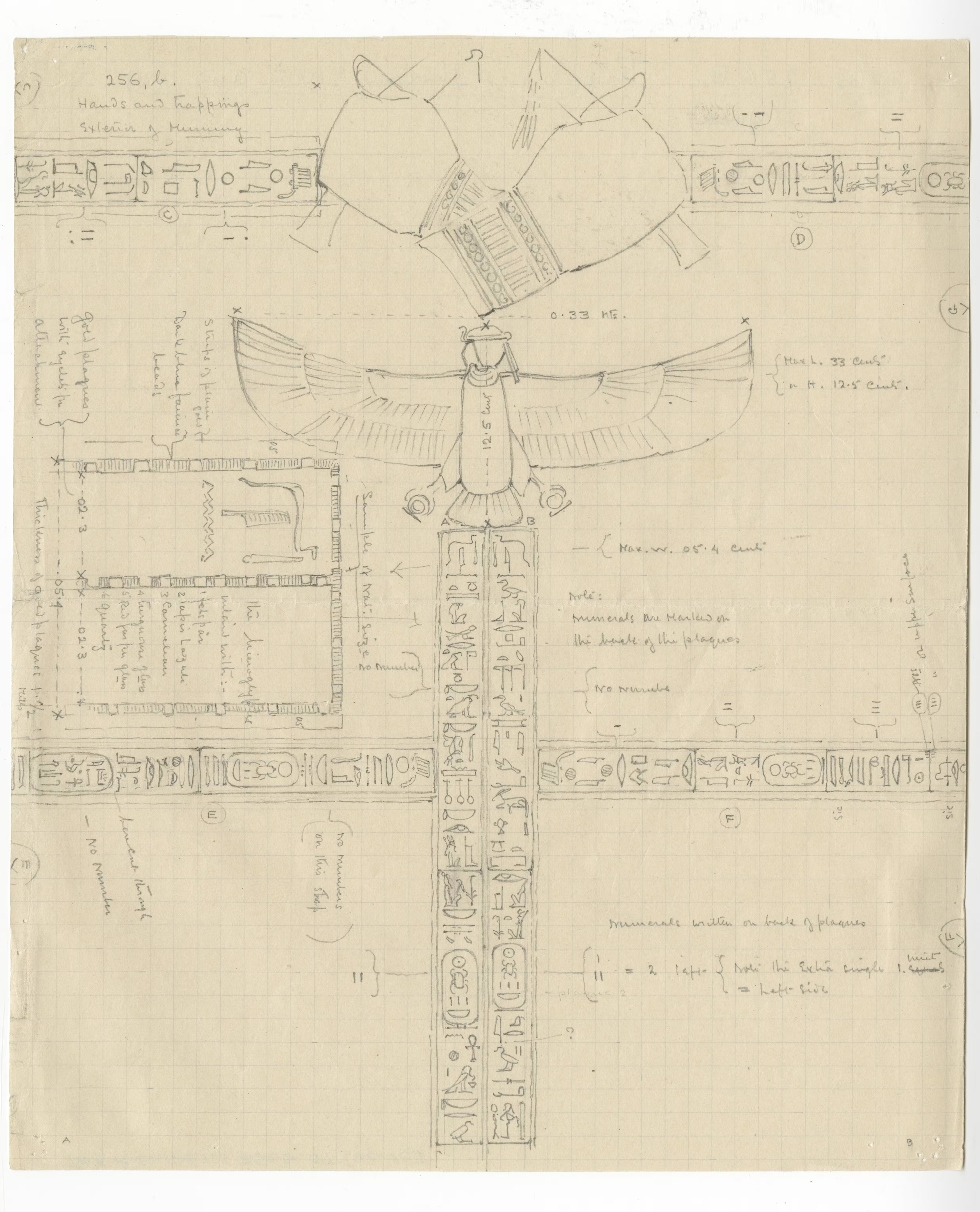

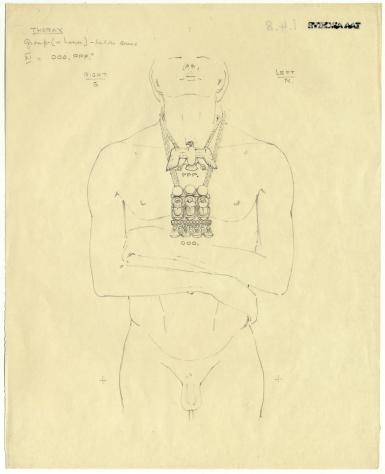

Howard Carter described the objects and their positions in meticulous notes and also produced a stunning set of 18 so-called “autopsy drawings”.

Together they form one of the most striking visual documents in the entire Tutankhamun archive, reflecting Carter’s artistic skill and his insistence on rigorous documentation even in moments of intense pressure.

Piecing the evidence

Once removed from the body, Lucas undertook initial cleaning and conservation, Burton then photographed the artefacts individually—creating the now-famous series of “studio photographs”—while Carter added detailed sketches and drawings.

Among these drawings are exquisite studies of the two daggers, one with a blade made of gold (256.dd), one of meteoritic iron (256.k).

By the end of the first day it was clear, as Carter recorded, “that we were dealing with the mortal remains of a young person.”

Four days later the doctors confirmed the age of the king to be about eighteen years at the time of his death.

Howard Carter’s drawing of the handle of the iron dagger (256.k) found on the body of Tutankhamun (TAA i.1.256.k.3.recto)

The significance of the unwrapping

The unwrapping of Tutankhamun’s body marked both the culmination of Carter’s work and one of the most carefully documented archaeological examinations ever undertaken.

The records produced in its process – Burton’s photographs, Lucas’s conservation reports, and Carter’s own drawings and notes, preserve the event with extraordinary immediacy and represent some of the most astonishing archaeological documents ever created.

How to cite

Griffith contributors, The Unwrapping of Tutankhamun’s mummified body, November 1925, Griffith Institute, 9 November 2025 URL

Be a part of our future!