Re-creating Tutankhamun’s Mask in 3D: From Harry Burton’s Photographs to a Digital Model

Since 2019, the Griffith Institute has collaborated with the University of St Andrews through the St Andrews Research Internship Scheme (StARIS), a programme designed to give undergraduate students sustained, hands on experience of academic research. One outcome of this collaboration has been the creation of a new 3D digital model of Tutankhamun’s funerary mask, produced entirely from the original photographic negatives taken by the expedition photographer Harry Burton during the excavation of the tomb in the 1920s.

This project represents, to our knowledge, the first attempt to generate a three-dimensional model directly from Burton’s original negatives, transforming early twentieth century excavation photography into a form suitable for modern digital analysis, preservation and visualisation.

Click here for the model

From Burton’s negatives to a digital reconstruction

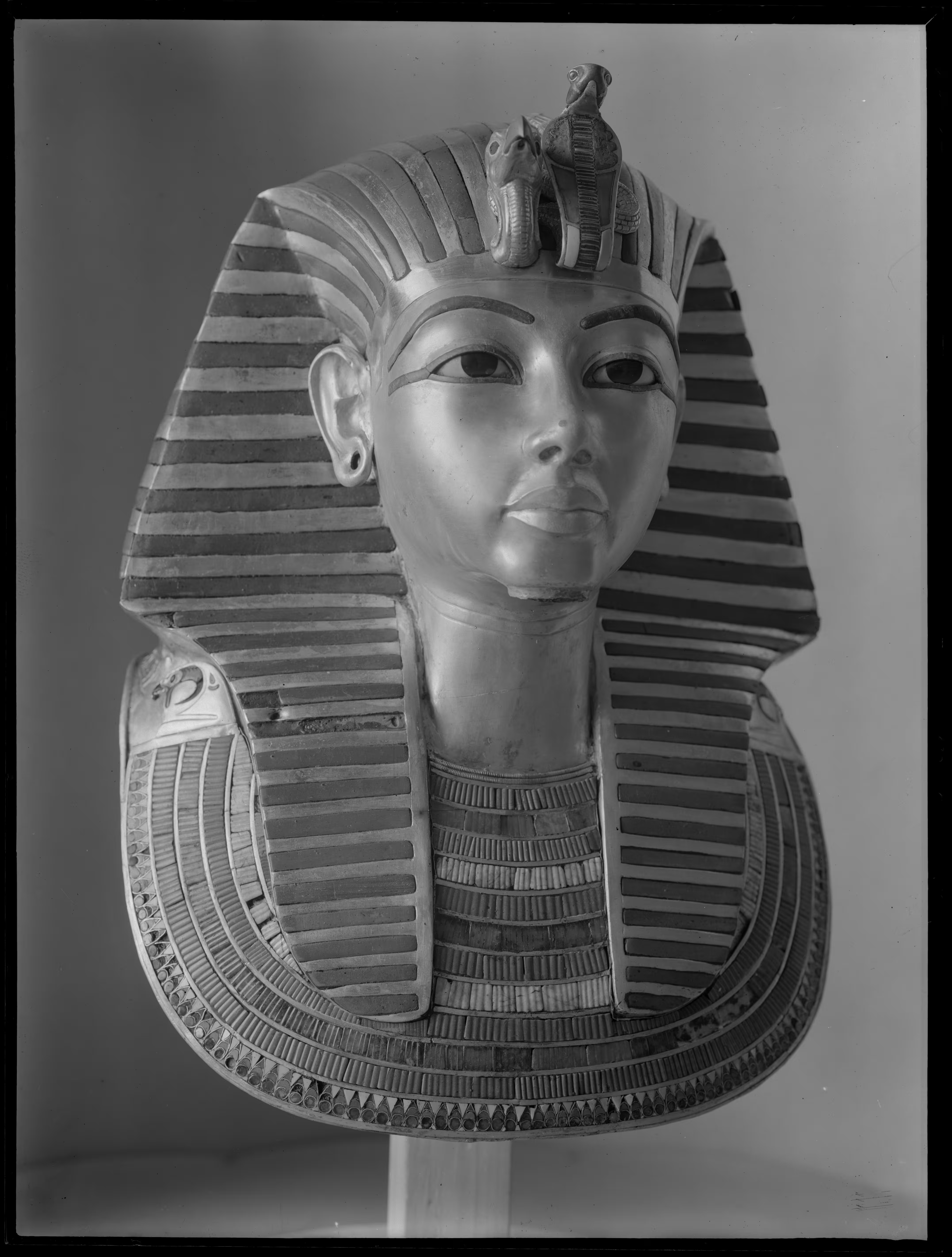

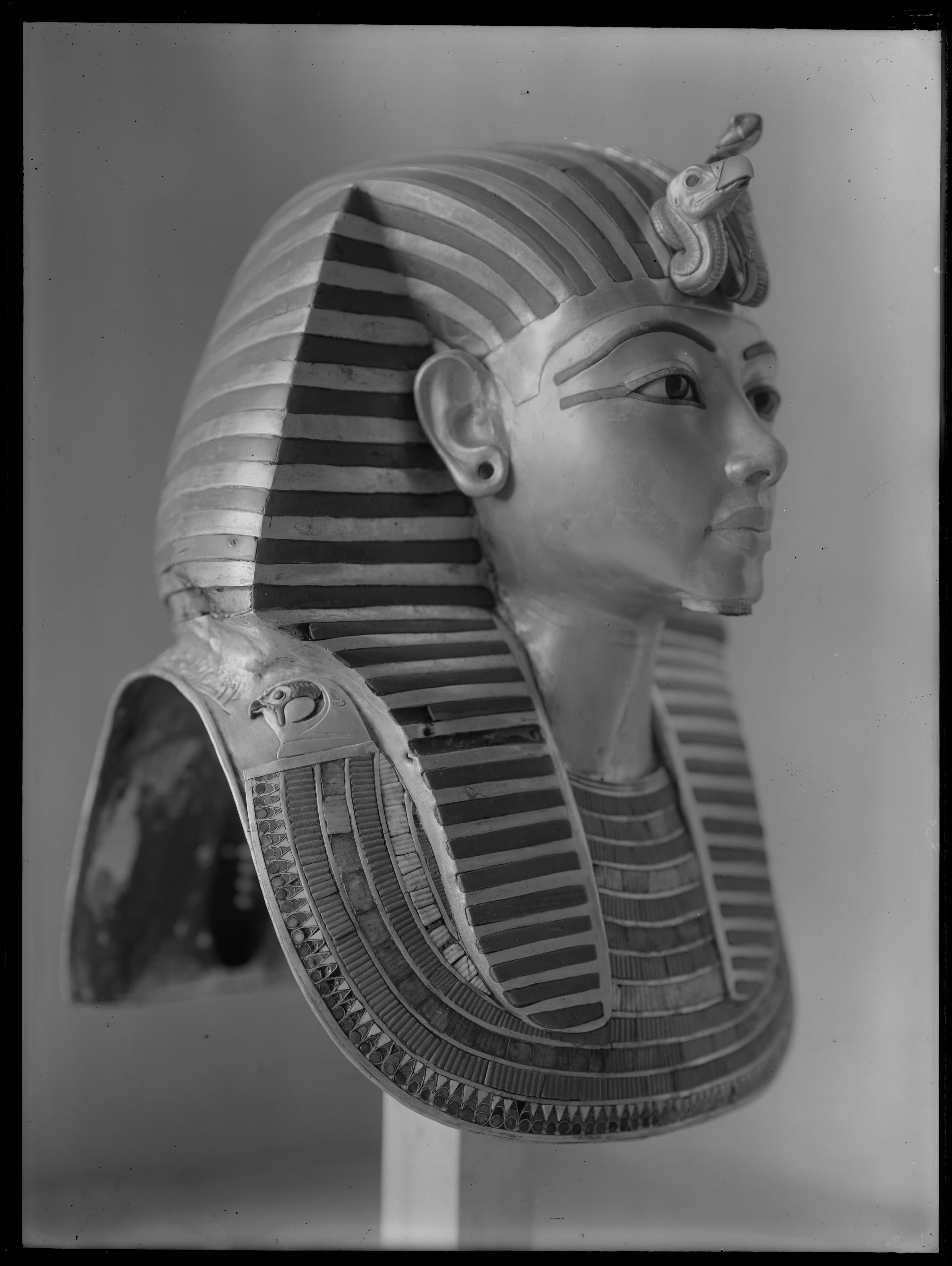

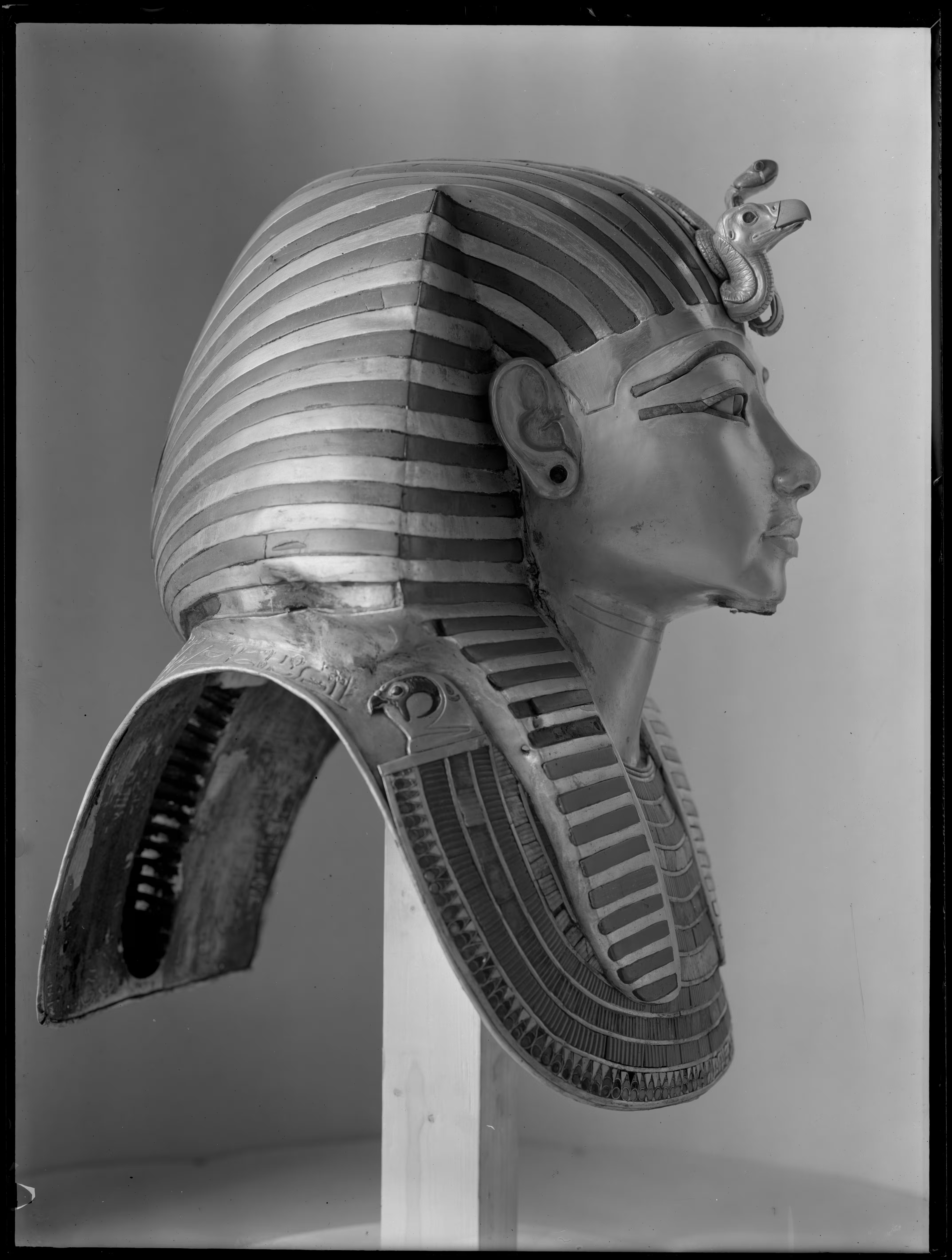

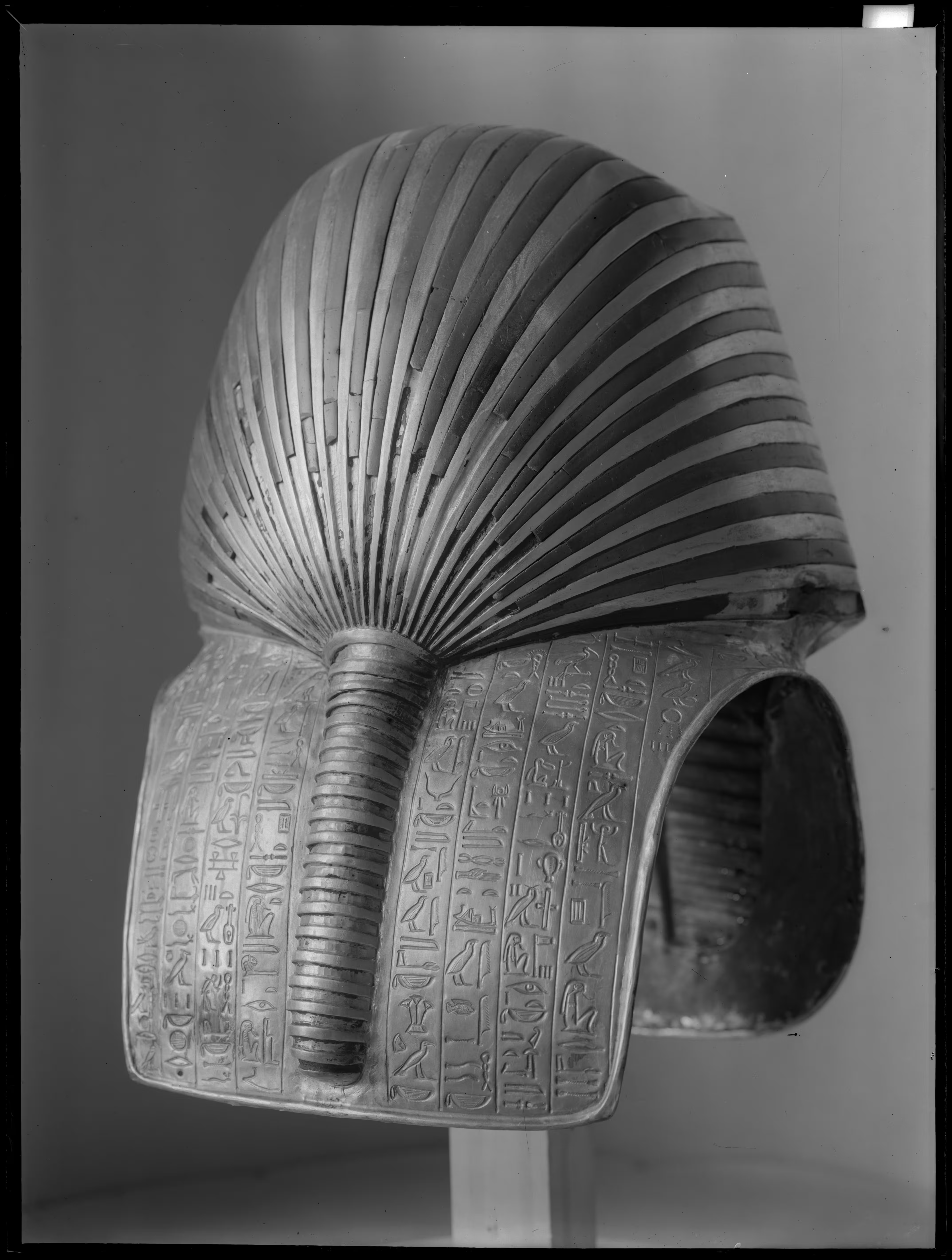

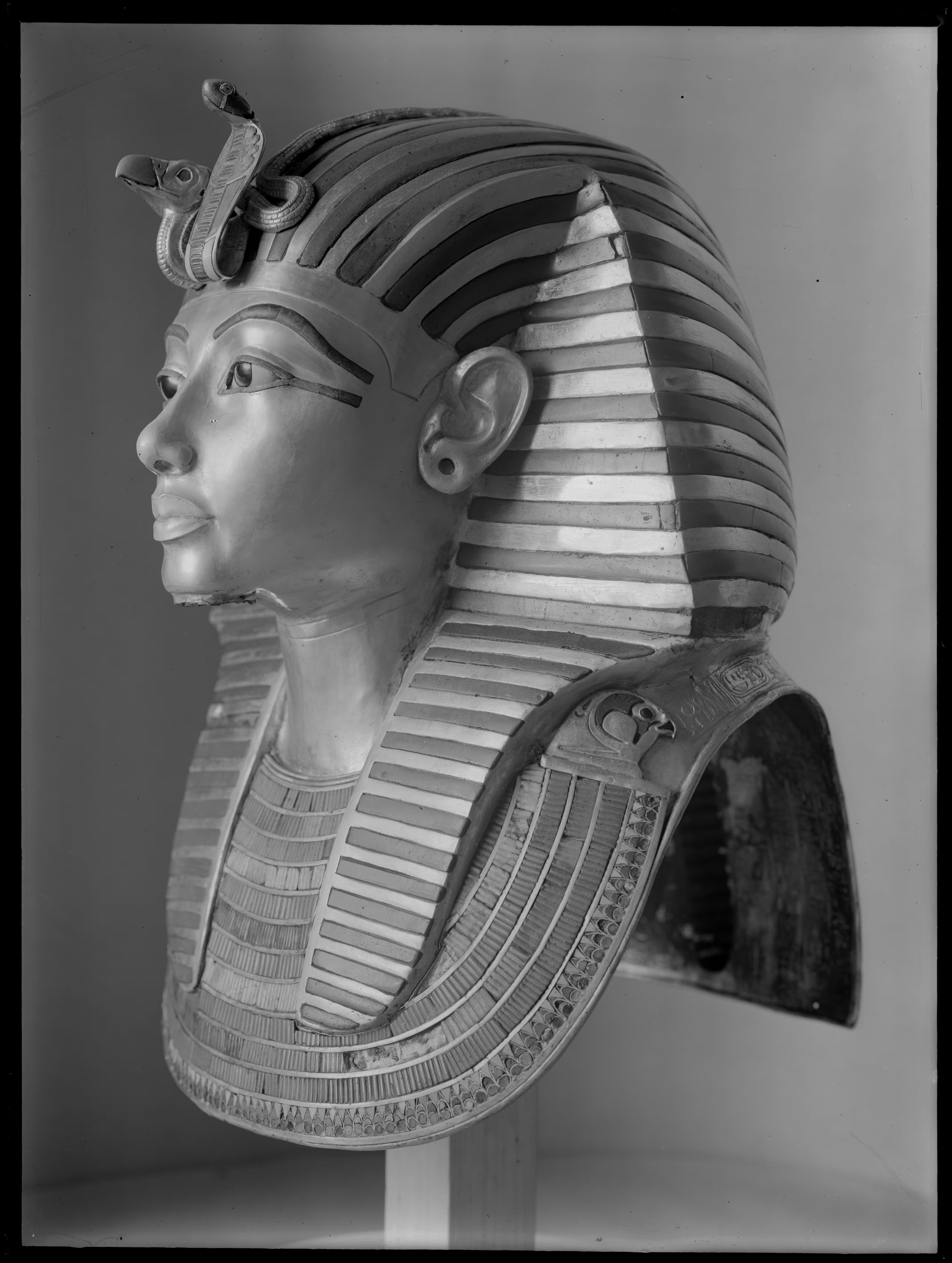

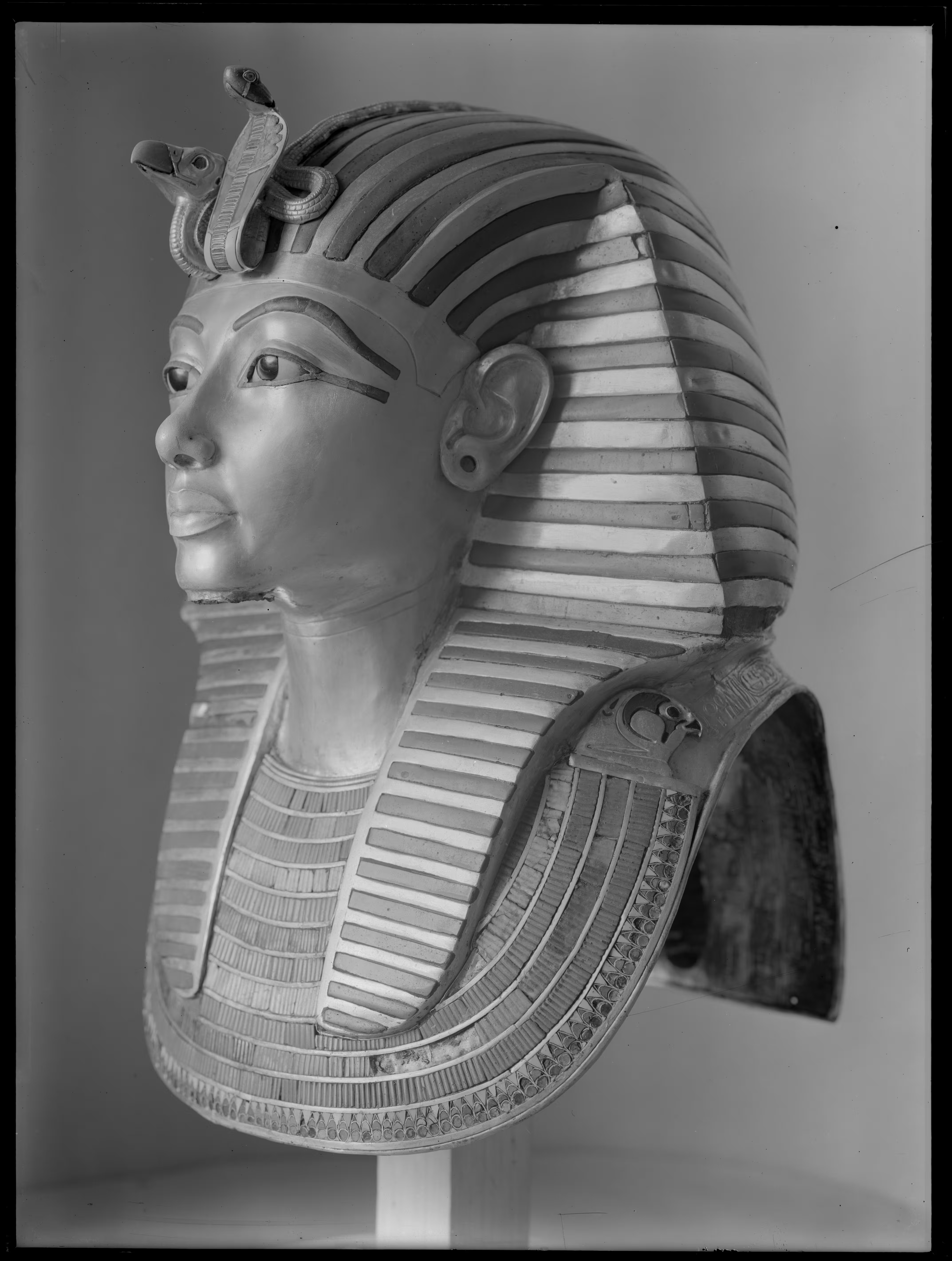

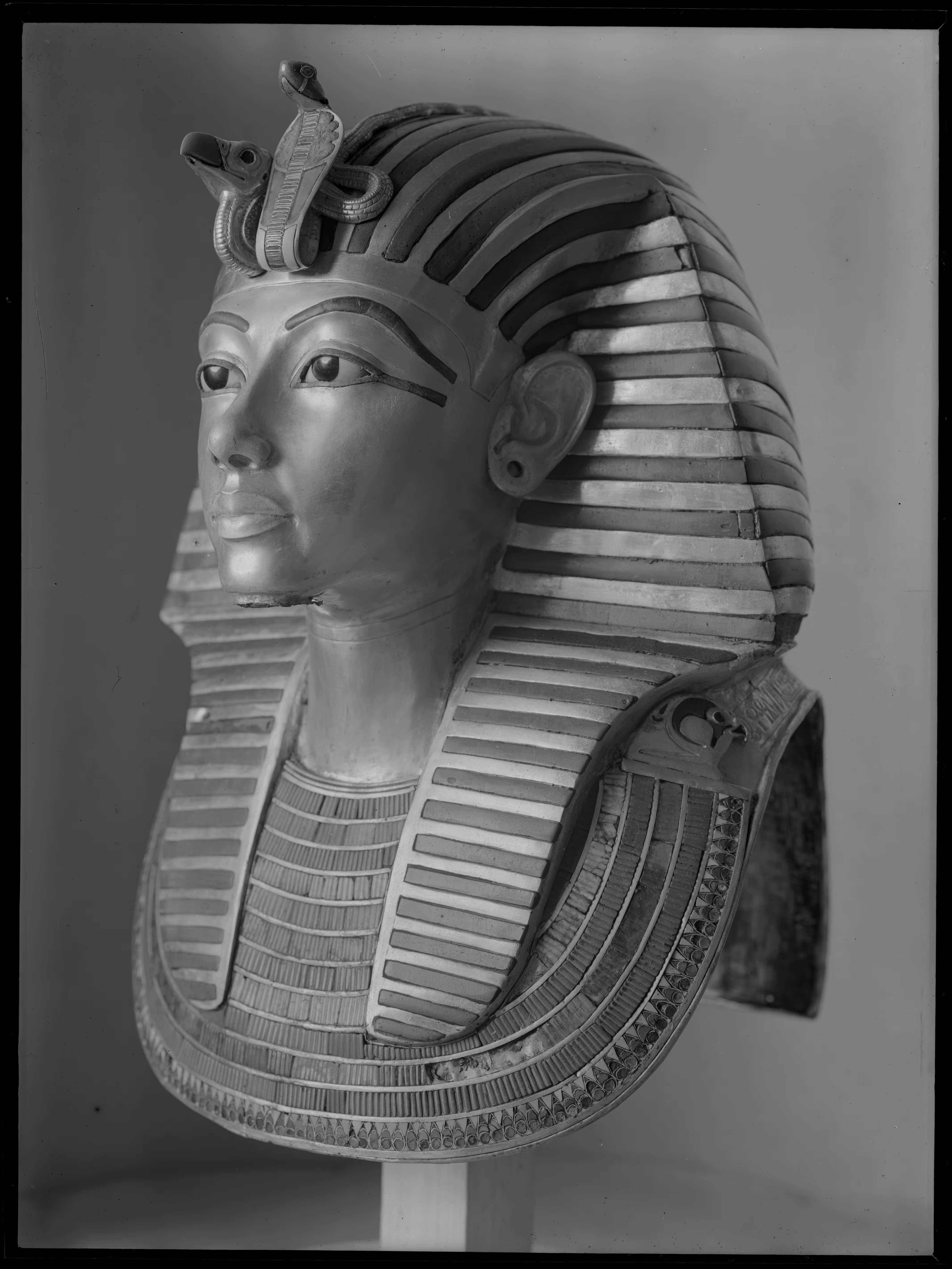

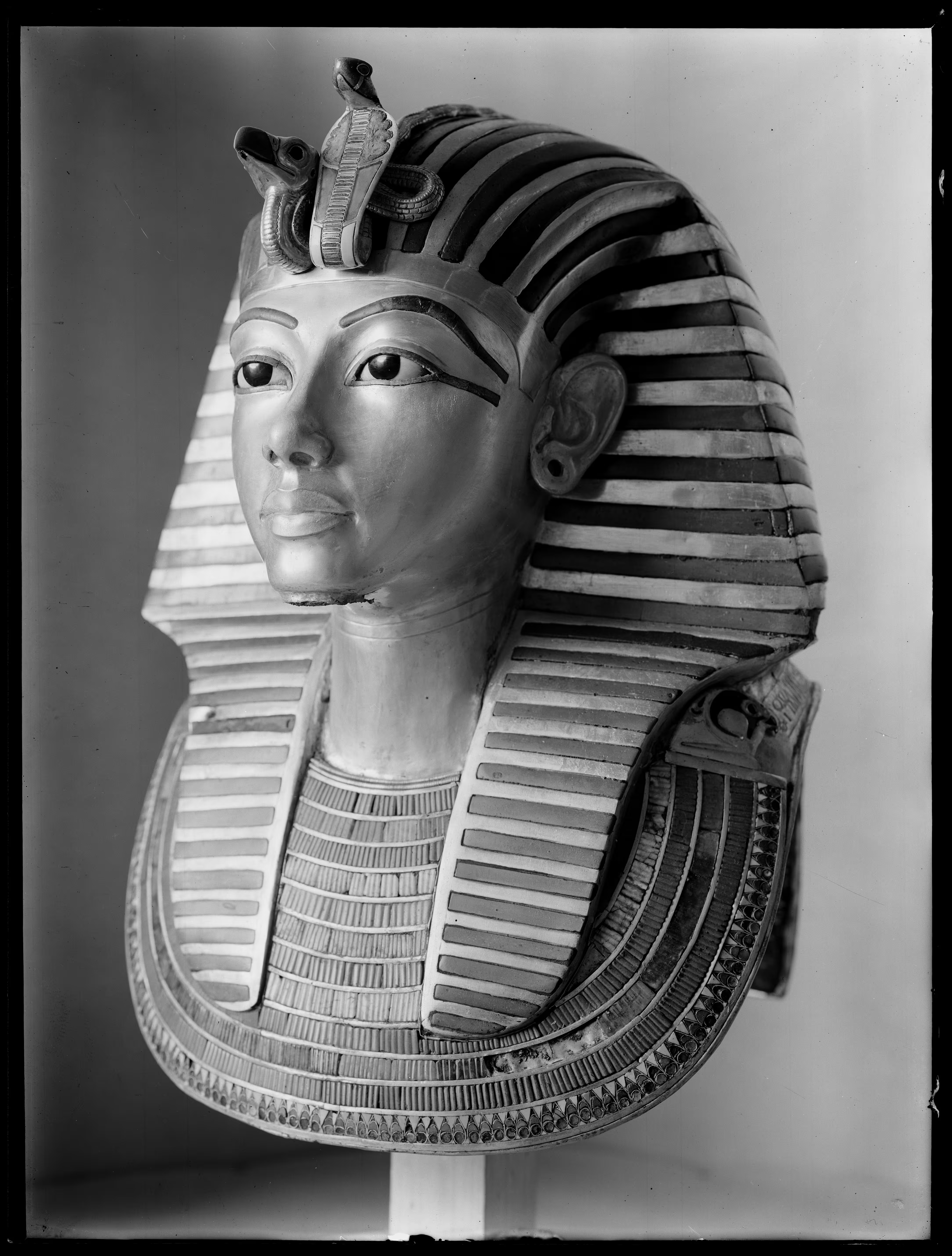

Burton captured more than twenty-five images of the mask during the excavation, some in situ on the king's mummified body, but most as controlled studio photographs taken in the nearby tomb of Sety II. Before photographing, he carefully removed the beard, mounted the mask on a stand, and applied a thin layer of paraffin wax to reduce the glare from its highly reflective gold surface. These remarkable glass-plate negatives provided the source material for the reconstruction.

The mask itself, the most iconic object from the tomb, weighs over 10 kilograms and is crafted primarily of gold, inlaid with coloured glass and gemstones such as lapis lazuli (eyebrows and eye surrounds), quartz (eyes), obsidian (pupils), carnelian, amazonite, turquoise, and faience.

“It was fascinating to see how much data could be recovered. Burton’s coverage of the right side meant we could mirror those forms and rebuild missing elements using Blender’s sculpting and lattice-modelling tools.”

Building the model

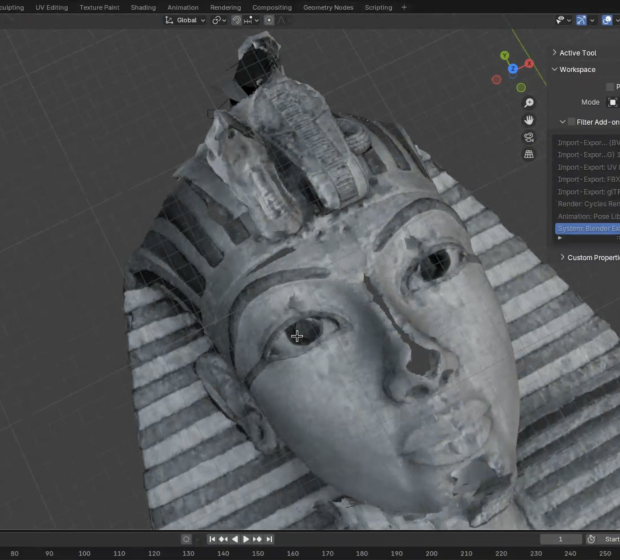

The modelling work was undertaken by Shikhar Srivastava, a St Andrews undergraduate intern, under the supervision of Dr Mark-Jan Nederhof (University of St Andrews) and Lara Bampfield (Griffith Institute, University of Oxford). Following extensive testing, the workflow was built entirely using open source software, principally Meshroom for photogrammetric processing and Blender for mesh refinement and reconstruction.

Photogrammetry pipelines were run on GPU enabled machines at the University of St Andrews, producing a high density textured mesh. This initial output required significant post processing. While the right hand side of the mask was well captured in Burton’s photographs, coverage of the left side was more limited, resulting in distortion and lacunae in the initial mesh.

Within Blender, malformed areas were selectively removed and reconstructed using a combination of mirroring, manual alignment, and sculpting tools. Where symmetry could be reasonably assumed, well preserved elements were duplicated and mirrored. Where lens distortion introduced geometric warping, lattice modifiers were used to correct the underlying geometry, compensating for the absence of original camera metadata in the scanned negatives.

The result is a visually coherent model that preserves the surface character and proportions of the mask as recorded by Burton, while remaining transparent about the limits of the underlying data.

Challenges and discoveries

Working from historic photographs presents particular challenges. Variations in exposure, incomplete circumferential coverage, and the lack of lens metadata all affect the reliability of photogrammetric reconstruction. In addition, the mask is not fully symmetrical, notably due to the vulture and cobra elements adorning the king's forehead, which restricts the use of global mirroring approaches.

Shikhar notes “Unlike coding, Blender doesn’t automatically store version histories. If I did it again, I’d definitely implement a version-tracking system to avoid overwriting earlier work.”

The current model prioritises surface representation and visual continuity rather than volumetric completeness. While suitable for digital display and comparative study, it is not intended for physical reproduction, such as 3D printing, without further substantial re processing.

Throughout the project, careful attention was paid to documenting decisions and limitations, ensuring that reconstructed elements can be distinguished conceptually from those directly supported by photographic evidence.

Current state and future directions

The present model represents the front and lateral surfaces of the mask. The back and upper crown are not preserved in the photographic record and are therefore treated conservatively. These areas have been closed or stabilised visually to support display, but they do not attempt a detailed reconstruction of undocumented surfaces.

Parallel experimental work at St Andrews has explored alternative modelling approaches and combinations of datasets. These models are currently hosted temporarily for internal development and testing and are not yet intended as public reference versions.

Future work will investigate whether additional archival material, including excavation measurements and drawings, could support more explicit modelling of missing areas, as well as how similar workflows might be applied to other objects from the tomb.

As this project demonstrates, historic excavation archives remain an active source of new knowledge. By combining Burton’s photography with modern computational methods, it is possible not only to preserve these records, but also to reinterpret them in ways that were never envisaged at the time of their creation.

“This project shows what can be achieved when historical archives meet modern computing. It brings us closer to experiencing Tutankhamun’s burial assemblage as Burton and Carter saw it, but now in three dimensions.”

3D reconstruction: Shikhar Srivastava (University of St Andrews)

Supervision: Dr Mark-Jan Nederhof (University of St Andrews) Lara Bampfield (Griffith Institute, University of Oxford)

Photographs: Harry Burton, The Griffith Institute Archive

Collaboration: St Andrews Research Internship Scheme (StARIS)

How to cite

Lara Bampfield and Shikhar Srivastava, Re-creating Tutankhamun’s Mask in 3D: From Harry Burton’s Photographs to a Digital Model, Griffith Institute, 6 November 2025 URL