Preserving a Fragile Memory: The Funeral Wreath of Tutankhamun

Take a closer look at one of the most delicate objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb as seen on the right via a modern replica.

As winter approaches and wreaths appear in homes, public spaces, and places of remembrance, they often serve as quiet symbols of continuity, care, and reflection. These traditions, though shaped by different cultures and beliefs, share a long history. One of the most moving examples survives from ancient Egypt: a small and fragile garland placed on the forehead of the young king Tutankhamun at his burial.

When Howard Carter and his team entered the tomb of Tutankhamun, they encountered nearly 6,000 objects, each demanding time, care, and patience to record. The clearance of the tomb was slow and exacting, not only because of the sheer quantity of material, but because so much of it was extraordinarily fragile. Alongside the famous gold and semi precious stones were objects made of wood, cloth, foodstuffs, and flowers, traces of everyday life carefully prepared for eternity.

Among these items was something especially intimate: a tiny garland of cornflowers and olive leaves, placed gently on the young king’s forehead on his outer coffin.

It may have been laid there by priests, or perhaps by Tutankhamun’s widow, in a final, personal act of farewell. Simple in form, yet rich in meaning, the wreath reminds us that even in moments of royal ceremony, human gestures of care and remembrance mattered deeply.

By the time it was discovered, the garland was so brittle that it could not be touched. Yet thanks to the foresight of the excavation team, it was carefully recorded through photographs taken by Harry Burton in 1925. Preserved by the dry, sealed environment of the tomb, the withered flowers still retained a hint of colour, allowing their quiet beauty to be captured and shared.

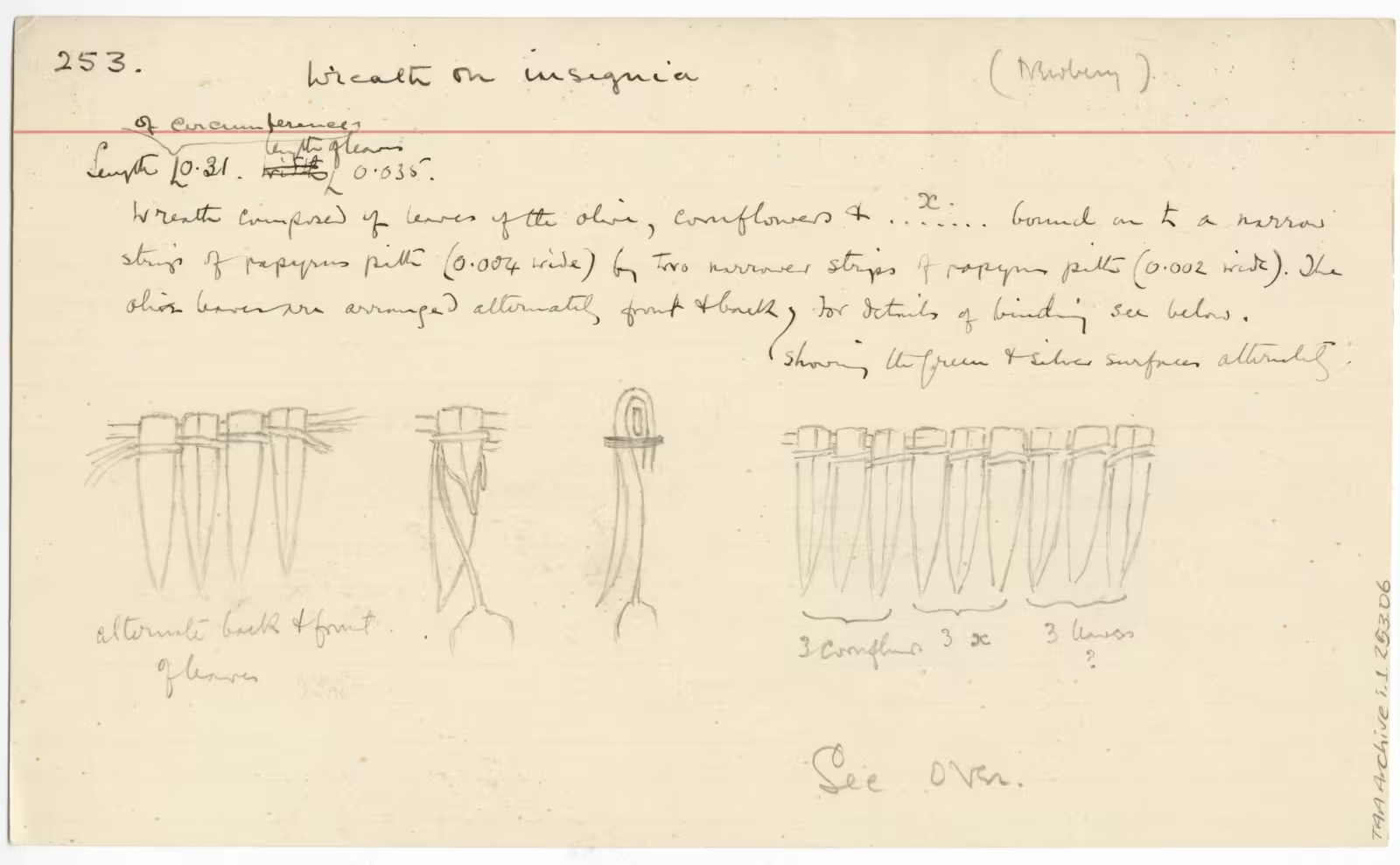

Object card TAA i.1.253.06 written by Newberry discussing the wreath

Further details were recorded on object cards prepared by Howard Carter and the team’s botanist Percy Newberry.

The olive leaves had been arranged to alternate between their green upper surfaces and silvery undersides. Leonard A. Boodle of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, identified the plants as “Leaves of olive (Olea Europaea, Linn.), and flowers of Centaurea depressa, Bieb. (Resembling Blue Cornflower)”.

Carter himself was deeply moved by this wreath. Writing later, he reflected that amid all the splendour of gold and royal regalia, nothing affected him more than these few flowers. To him, they collapsed the distance between past and present, reminding modern viewers that the people of ancient Egypt shared the same impulses to honour, remember, and care for one another.

“But perhaps the most touching of all was the fact that around those emblems was a tiny wreath of flowers. I can assure you, among all that regal splendour, that royal magnificence, everywhere the glint of gold, there was nothing so touching as those few withered flowers, still retaining their tinge of colour, they told us what a short period three thousand three hundred years really was – but Yesterday and the Morrow. In fact, that little touch of nature made that ancient and our modern civilization kin.”

Ahdaf Soueif placing the wreath before a display honouring the Egyptian members of the excavation team during the Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive exhibition.

Nearly a century later, this sense of connection inspired a new act of remembrance. In the summer of 2022, the Griffith Institute commissioned a replica of the garland. Using Burton’s photographs and Newberry’s drawings, the florists of The Garden of Oxford were able to recreate the wreath, bringing fresh life to a gesture first made over 3,300 years ago.

The replica was unveiled during a small commemorative ceremony marking the centenary of the opening of the tomb’s Antechamber during the exhibition Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive (Weston Library, 13th April 2022 – 5th February 2023). Placed by Ahdaf Soueif before a display honouring the Egyptian members of the excavation team, the wreath became a focal point for reflection, not only on the death of a young king, but on the many lives, ancient and modern, connected through this extraordinary discovery.

Burton Photograph of the wreath placed on the outer coffin

Today, the replica garland forms part of the Tutankhamun archive at the Griffith Institute.

Quiet and unassuming, it endures to speak of care, continuity, and shared humanity. Encountered at a time of year traditionally associated with wreaths, remembrance, and gathering, it invites reflection on how such gestures transcend period and belief. In both ancient and modern contexts, the act of laying a wreath remains a simple but powerful way of honouring life, memory, and human connection.

How to cite

Griffith Institute, Preserving a Fragile Memory: The Funeral Wreath of Tutankhamun, Griffith Institute, 12 December 2025 URL

Be a part of our future!