TAA i.3.23.21

Page 9 of first draft on shrines, handwritten.

The whole text or part of the text is fully struck through on this page but is not indicated in the transcription. On this page, strikethrough formatting is reserved for the author’s edits and deletions within the main body of the text, which would otherwise be difficult to distinguish.

© Griffith Institute,

University of Oxford

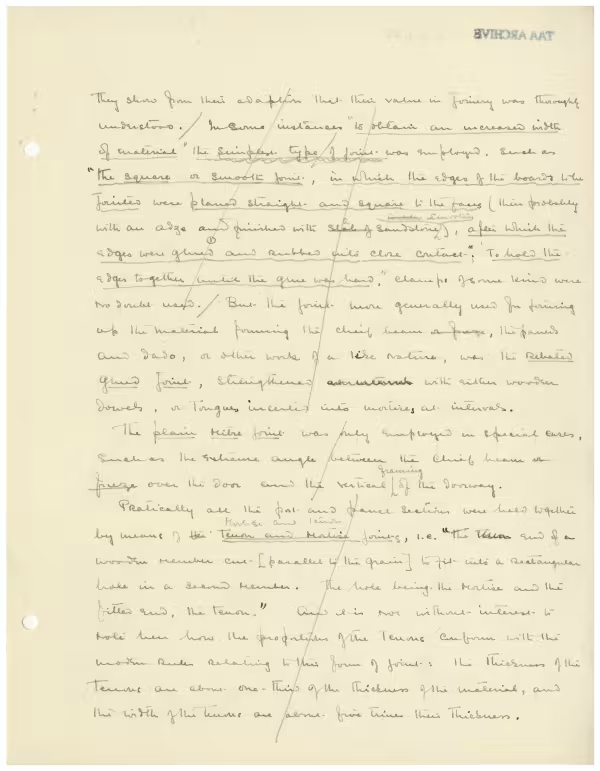

They show from their adaption that their value in joinery was thoroughly

understood. / In some instances “to obtain an increased width

of material” the simplest type of joint was employed, such as

“the square or smooth joint, in which the edges of the boards to be

jointed were planed straight and square to the faces (then probably

with an adze and finished with slab of/<a> sandstone <Rubber/smoother>), after which the

edges were glued and rubbed into close contact”; to hold the

edges together until the glue was hard”, clamps of some kind were

no doubt used. / But the joint more generally was used for joining

up the material forming the chief beam or frieze, the panels

and dado, or other work of a like nature, was the rebated

glued joint, strengthened at xxx[?] with either wooden

dowels, or tongues inserted into mortises at intervals.

The plain mitre joint was only employed in special cases,

such as the extreme angle between the chief beam or

frieze over the door and the vertical <framing> of the doorway.

Practically all the post and panel sections were held together

by means of thetenon and mortise/<mortise and tenon> joints, – i.e. “The x[?] end of a

wooden member cut [parallel to the grain] to fit into a rectangular

hole in a second member. The hole being the mortise and the

fitted end, the tenon.” And it is not without interest to

note here how the proportions of the tenons conform with the

modern rules relating to this form of joint: the thickness of the

tenons are about one-third of the thickness of the material, and

the width of the tenons are about five times their thickness.